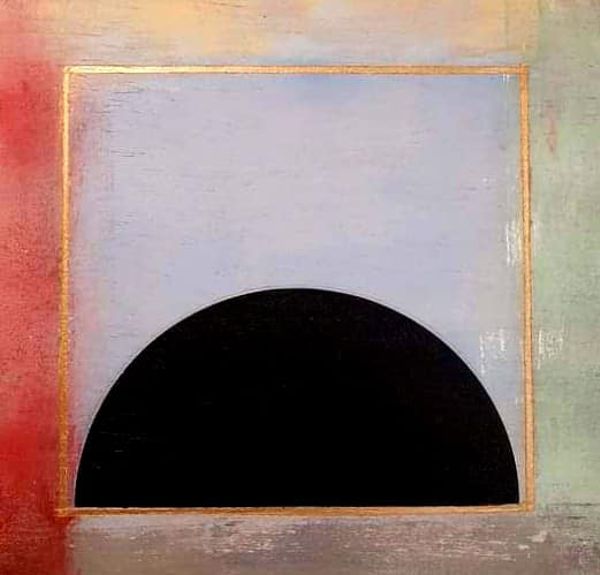

About his work

A Complete Painting

It’s important to specify the physical context in which Gilles Courbière has been creating his work recently: on the table in a small room in his flat. After making his sculptures for several years in a spacious studio, his landlord’s failure to renew the rent forced him to move back into his own home to continue his work. With his physical possibilities limited, he was forced to reduce the size of his works and simplify their execution. He also decided on a project that he had been thinking about for a long time but had never dared to tackle until now, at least not in this way: making paintings. In the end, these circumstances were decisive in the face of a new series, just as the confinement contributed decisively to this adaptation. He therefore focused on creating paintings of restricted dimensions. These are small boxes framing a variety of shapes and figures and although they are mainly painted in acrylic, each of the pieces in the series always starts from an outline, sometimes an elementary one. Improvisation, however, also plays a fundamental role, and each work takes shape at the same pace as its own creation. For this reason, and because it is the very idea of the project, all the appearances, shapes and colours are different. Some are ordered and others chaotic, some are systematic and others regular like neoplasticism and others are at the opposite pole. Although the colours are normally matt, he sometimes uses metallic colours with iridescent reflections. The propositions that each painting contains are antagonistic relationships, and this is the general idea, the starting point of the whole: different shapes and colours must produce infinite results. A heterogeneity that responds to the experimental nature of his paintings and incorporates all sorts of shapes such as squares, circles and triangles, sometimes opposites, sometimes symmetrical, always opposites. Despite this dissimilarity of forms, I think that what weighs most heavily on this series is the influence of reductionist styles, such as Suprematism and Constructivism (or the Orphist branch that the Delaunays created). Sol LeWitt’s pictorial proposals are also a long-standing influence for him, as well as Japanese art, which still counts in the development of his paintings, far from Expressionism and its areas of influence. In all his work in general there is a fruitful tension between form and colour. It’s inevitable to imagine that on this occasion also, he’s looking for that same tension of polychromy and conformation, in a particular way, and giving it the most importance. This is not the first time he has worked with this confrontation between form and colour. From his earliest sculptures, now long gone, polychromed in muted hues, colour has always been present and it has become increasingly important, as a recent series demonstrates, Dégradés, which I am tempted to regard as an indisputable precedent for these paintings, for there is a similar tension here between the geometry of forms and the presence of colour, between calculation and the most immediate sensuality. The relationship and differences with the gradients is therefore obvious, as is the intensity of the colours in this sculptural series; the paint is softer on the gradients, but bolder in his paintings. They seek more complex harmonies in their respective relationships, and they blend together, whereas in the gradients they offer limited, spatially separated fields of colour. The surfaces in this series are composed of several layers, two or three at most. Sometimes, deliberately, relief creeps in. This is not accidental, as the temptation is fulfilled to offer a kind of precise space – the sculptor’s instinct. We find different layers and textures, subtly arranged and posing differences of space and appearance in each work (in some, this relationship is not so subtle but more obvious). Sometimes these are latent images, or also colours, which eventually emerge. Sometimes isolated layers of oil paint are added to the acrylic paint to thicken the relief; this is also a spatial clue to be taken into account. If we try to rediscover the essence of the series, we will see that, although their creator called them paintings, and colour is an essential element, the nature of the sculptor, the one who works with space, emerges through them. The relationship between painting and sculpture takes over. Basically, Gilles Courbière has asserted that although these are simple paintings, they are undeniably constructed like reliefs. Sometimes he sands the surface to provide different levels or spaces. By sanding with sandpaper, he makes excavations, a common process in sculpture. In fact, the synthesis between this and painting is obvious when you learn that the pieces are only considered finished by their author after successive processes of sanding and painting. I’ve always referred to these works as paintings or reliefs, but in the end, they are boxes. They have a frame that surrounds them and gives them depth (like open windows that you can imagine). And don’t miss the fact that on these windows, there are coloured lines that surround the main image. Inspired by medieval paintings – some Persian, but also Christian – they end up reconfiguring the work and giving it the status of an object, a complete painting.

Pablo Llorca